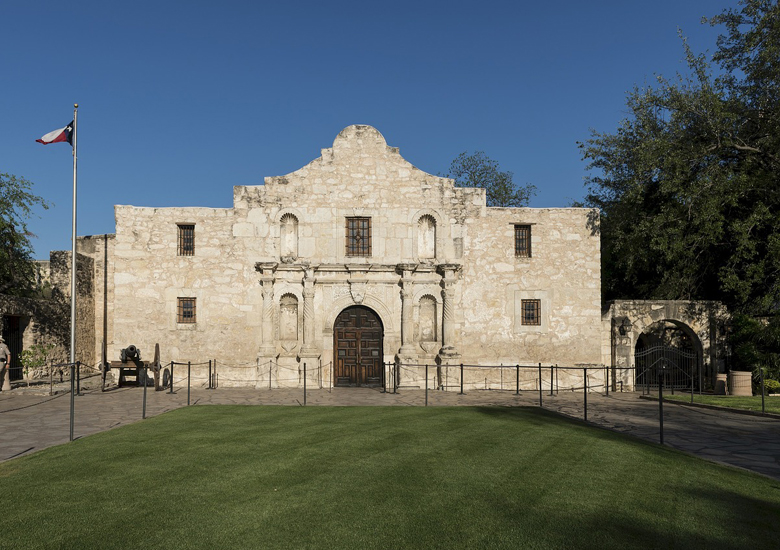

The Alamo Mission in San Antonio is commonly called The Alamo and was originally known as Mision San Antonio de Valero. It was founded in the 18th century as a Roman Catholic mission and fortress compound, and today is part of the San Antonio Missions World Heritage Site in San Antonio, Texas.-U.S.A.

It was the site of the Battle of the Alamo in 1836, and is now a museum in the Alamo Plaza Historic District. The compound was one of the early Spanish missions in Texas, built for the education of area American Indians after their conversion to Christianity. The mission was secularized in 1793 and then abandoned. Ten years later, it became a fortress housing the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras military unit, who likely gave the mission the name Alamo.

During the Texas Revolution, Mexican General Martin Perfecto de Cos surrendered the fort to the Texian Army in December 1835, following the Siege of Bexar. A relatively small number of Texian soldiers then occupied the compound for several months. They were wiped out at the Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836. When the Mexican army retreated from Texas several months later, they tore down many of the Alamo walls and burned some of the buildings.

For the next five years, the Alamo was periodically used to garrison soldiers, both Texian and Mexican, but was ultimately abandoned. In 1849, several years after Texas was annexed to the United States, the U.S. Army began renting the facility for use as a quartermaster’s depot. The U.S. Army abandoned the mission in 1876 after nearby Fort Sam Houston was established. The Alamo chapel was sold to the state of Texas, which conducted occasional tours but made no effort to restore it. The remaining buildings were sold to a mercantile company which operated them as a wholesale grocery store.

The Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) formed in 1895 and began trying to preserve the Alamo. Adina Emilia De Zavala and Clara Driscoll successfully convinced the state legislature in 1905 to purchase the remaining buildings and to name the DRT as the permanent custodian of the site. Over the next century, periodic attempts were made to transfer control of the Alamo from the DRT. In early 2015, Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush officially removed control of the Alamo to the Texas General Land Office.

The Alamo and the four missions in the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park were designated UNESCO World Heritage sites on July 5, 2015.

History : Mission : In 1716, the Spanish government established several Roman Catholic missions in East Texas. The isolation of the missions—the nearest Spanish settlement, San Juan Bautista, Coahuila was over 400 miles (644 km) away—made it difficult to keep them adequately provisioned. To assist the missionaries, the new governor of Spanish Texas, Martin de Alarcon, wished to establish a way station between the settlements along the Rio Grande and the new missions in East Texas. In April 1718, Alarcon led an expedition to found a new community in Texas. On May 1, the group erected a temporary mud, brush, and straw structure near the headwaters of the San Antonio River. This building would serve as a new mission, San Antonio de Valero, named after Saint Anthony of Padua and the viceroy of New Spain, Baltasar de Zuniga y Guzman Sotomayor y Sarmiento, Marquess of Valero. The mission, headed by Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares, was located near a community of Coahuiltecans and was initially populated by three to five Indian converts from Mission San Francisco Solano near San Juan Bautista. One mile (two km) north of the mission, Alarcon built a presidio (fort), the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar. Close by, he founded the first civilian community in Texas, San Antonio de Bexar (now San Antonio, Texas).

Within a year, the mission moved to the western bank of the river, where it was less likely to flood. Over the next several years, a chain of missions were established nearby. In 1724, after remnants of a Gulf Coast hurricane destroyed the existing structures at Mission San Antonio de Valero, the mission was moved to its current location. At the time, the new location was just across the San Antonio River from the town of San Antonio de Bexar, and just north of a group of huts known as La Villita.

Over the next several decades, the mission complex expanded to cover 3 acres (1.2 ha). The first permanent building was likely the two-story, L-shaped stone residence for the priests. The building served as parts of the west and south edges of an inner courtyard. A series of adobe barracks buildings were constructed to house the mission Indians and a textile workshop was erected. By 1744, over 300 Indian converts resided at San Antonio de Valero. The mission was largely self-sufficient, relying on its 2000 head of cattle and 1300 sheep for food and clothing. Each year, the mission’s farmland produced up to 2000 bushels of corn and 100 bushels of bean cotton was also grown

The first stones were laid for a more permanent church building in 1744, however, the church, its tower and the sacristy collapsed in the late 1750s. Reconstruction began in 1758, with the new chapel located at the south end of the inner courtyard. Constructed of 4 feet (1.2 m) thick limestone blocks, it was intended to be three stories high, topped by a dome, with bell towers on either side. Its shape was a traditional cross, with a long nave and short transepts. Although the first two levels were completed, the bell towers and third story were never begun. While four stone arches were erected to support the planned dome, the dome itself was never built. As the church was never completed, it is unlikely that it was ever used for religious services.

The chapel was intended to be highly decorated. Niches were carved on either side of the door to hold statues. The lower-level niches displayed Saint Francis and Saint Dominic, while the second-level niches contained statues of Saint Clare and Saint Margaret of Cortona. Carvings were also completed around the chapel’s door.

Up to 30 adobe or mud buildings were constructed to serve as workrooms, storerooms, and homes for the Indian residents. As the nearby presidio was perpetually understaffed, the mission was built to withstand attacks by Apache and Comanche raiders. In 1745, 100 mission Indians successfully drove off a band of 300 Apaches which had surrounded the presidio. Their actions saved the presidio, the mission, and likely the town from destruction. Walls were erected around the Indian homes in 1758, likely in response to a massacre at the San Saba mission. The convent and church were not fully enclosed within the 8 feet (2.4 m) walls. The walls were built 2 feet (0.61 m) thick and enclosed an area 480 feet (150 m) long (north-south) and 160 feet (49 m) wide (east-west). For additional protection, a turret housing three cannon was added near the main gate in 1762. By 1793 an additional one-pounder cannon had been placed on a rampart near the convent.

The population of Indians fluctuated, from a high of 328 in 1756 to a low of 44 in 1777. The new commandant general of the interior provinces, Teodoro de Croix, thought the missions were a liability and began taking actions to decrease their influence. In 1778, he ruled that all unbranded cattle belonged to the government. Raiding Apache tribes had stolen most of the mission’s horses, making it difficult to round up and brand the cattle. As a result, when the ruling took effect, the mission lost a great deal of its wealth and was unable to support a larger population of converts. By 1793, only 12 Indians remained. By this point, few of the hunting and gathering tribes in Texas had not been Christianized. In 1793, Mission San Antonio de Valero was secularized.

Shortly after, the mission was abandoned. Most locals were uninterested in the buildings. Visitors were often more impressed. In 1828, French naturalist Jean Louis Berlandier visited the area. He mentioned the Alamo complex: “An enormous battlement and some barracks are found there, as well as the ruins of a church which could pass for one of the loveliest monuments of the area, even if its architecture is overloaded with ornamentation like all the ecclesiastical buildings of the Spanish colonies.

Military

In the 19th century, the mission complex became known as “the Alamo”. The name may have been derived from the grove of nearby cottonwood trees, known in Spanish as alamo. Alternatively, in 1803, the abandoned compound was occupied by the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras, from Alamo de Parras in Coahuila. Locals often called them simply the “Alamo Company”.

During the Mexican War of Independence, parts of the mission frequently served as a political prison. Between 1806 and 1812 it served as San Antonio’s first hospital. Spanish records indicate that some renovations were made for this purpose, but no details were provided.

The buildings were transferred from Spanish to Mexican control in 1821 after Mexico gained its independence. Soldiers continued to garrison the complex until December 1835, when General Martin Perfecto de Cos surrendered to Texian forces during the Texas Revolution. In the few months that Cos supervised the troops garrisoned in San Antonio, he had ordered many improvements to the Alamo. Cos’s men likely demolished the four stone arches that were to support a future chapel dome. The debris from these was used to build a ramp to the apse of the chapel building. There, the Mexican soldiers placed three cannon, which could fire over the walls of the roofless building. To close a gap between the church and the barracks (formerly the convent building) and the south wall, the soldiers built a palisade. When Cos retreated, he left behind 19 cannons, including a 16-pounder.

Battle of the Alamo

You can plainly see that the Alamo never was built by a military people for a fortress.

Letter, dated January 18, 1836, from engineer Green B. Jameson to Sam Houston, commander of the Texian forces.

With Cos’s departure, there was no longer an organized garrison of Mexican troops in Texas, and many Texians believed the war was over. Colonel James C. Neill assumed command of the 100 soldiers who remained. Neill requested that an additional 200 men be sent to fortify the Alamo, and expressed fear that his garrison could be starved out of the Alamo after a four-day siege. However, the Texian government was in turmoil and unable to provide much assistance. Determined to make the best of the situation, Neill and engineer Green B. Jameson began working to fortify the Alamo. Jameson installed the cannons that Cos had left along the walls.

Heeding Neill’s warnings, General Sam Houston ordered Colonel James Bowie to take 35–50 men to Bexar to help Neill move all of the artillery and destroy the fortress. There were not enough oxen to move the artillery someplace safer, and most of the men believed the complex was of strategic importance to protecting the settlements to the east. On January 26 the Texian soldiers passed a resolution in favor of holding the Alamo. On February 11, Neill went on furlough to pursue additional reinforcements and supplies for the garrison. William Travis and James Bowie agreed to share command of the Alamo.

On February 23 the Mexican army, under the command of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, arrived in San Antonio de Bexar. For the next thirteen days, the Mexican Army laid siege to the Alamo, during which work continued on the interior of the Alamo. After Mexican soldiers tried to block the irrigation ditch leading into the fort, Jameson supervised the digging of a well at the south end of the plaza. Although the men hit water, they weakened an earth and timber parapet near the barracks, collapsing it and leaving no way to fire safely over that wall.

The Fall of the Alamo, painted by Theodore Gentilz in 1844, depicts the final assault.

The siege ended in a fierce battle on March 6. As the Mexican army overran the walls, most of the Texians fell back to the long barracks (convent) and the chapel. During the siege, Texians had carved holes in many of the walls of these rooms so that they would be able to fire. Each room had only one door which led into the courtyard and which had been “buttressed by semicircular parapets of dirt secured with cowhides”. Some of the rooms even had trenches dug into the floor to provide some cover for the defenders. Mexican soldiers used the abandoned Texian cannon to blow off the doors of the rooms, allowing Mexican soldiers to enter and defeat the Texians.

The last of the Texians to die were the eleven men manning the two 12 lb (5.4 kg) cannon in the chapel. The entrance to the church had been barricaded with sandbags, which the Texians were able to fire over. A shot from the 18 lb (8.2 kg) cannon destroyed the barricades, and Mexican soldiers entered the building after firing an initial musket volley. With no time to reload, the Texians, including Dickinson, Gregorio Esparza, and Bonham, grabbed rifles and fired before being bayoneted to death. Texian Robert Evans was master of ordnance and had been tasked with keeping the gunpowder from falling into Mexican hands. Wounded, he crawled towards the powder magazine but was killed by a musket ball with his torch only inches from the powder. If he had succeeded, the blast would have destroyed the church.

Santa Anna ordered that the Texian bodies be stacked and burned. All, or almost all, of the Texian defenders were killed, although some historians believe that at least one Texian, Henry Warnell, successfully escaped from the battle. Warnell would die several months later of wounds incurred either during the final battle or during his escape. Most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. This would represent about one-third of the Mexican soldiers involved in the final assault, which historian Terry Todish stated, was “a tremendous casualty rate by any standards”

Access : Coordinates: 29.425833, -98.486111 / Location : 300 Alamo Plaza, San Antonio, TX 78205-2606 / The Alamo is about 20 minutes south of the airport and just steps away from the River Walk. You’ll find The Alamo nestled in the heart of downtown on Alamo Plaza, between E. Houston and Crockett streets. From here, you can hop on the Mission Reach hike & bike trail to explore more missions. The missions are accessible by VIA bus line 42 and VIVA bus line 40. Visit the linked webpages for more information.

Free Admission.

Hours : Peak Season (May 25 – Sept. 3): 9 a.m. – 7 p.m. / Off-Peak Season (Sept. 4 – May 24): 9 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. / Extended Holiday hours (Nov. 30 – Dec. 30): 9 a.m. – 7 p.m. Monday – Thursday, 9 a.m. – 8 p.m. Friday – Sunday /Last entry 15 minutes before close / Closed Christmas Day